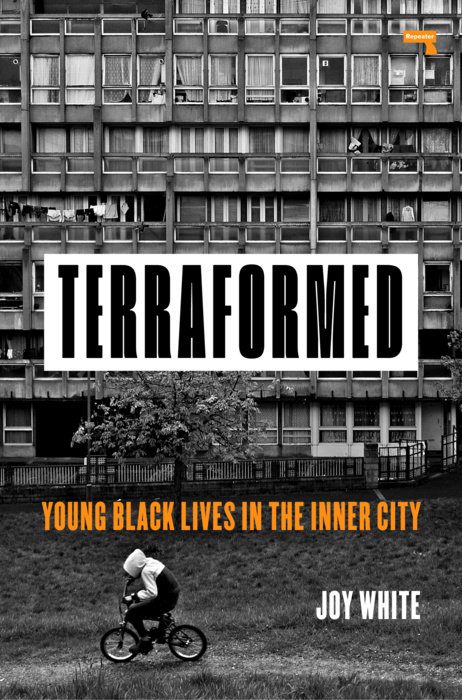

Joy White’s Terraformed is introduced and framed as a part (urban) ethnography, part memoir telling the story of young Black lives in inner city London. The author’s research and fieldwork take place in the urban setting of Forest Gate, a diverse, multicultural neighborhood located in the East London suburb of Newham. In this ethnographic study, White seeks to “contextualize the history of Newham and consider how young Black lives are impacted by racism, neoliberal policy, and austerity” (p. 5). She argues that the paradigm of neoliberalism and the discourse of meritocracy that underpins it, alongside the “austerity programme”, have deepened inequality instead of reducing it, notably at the expense of Black youth. Based on her own developed framework referred to as “hyper-local demarcation”, White’s study investigates these processes and techniques through the arenas of legislation, communities, the sonic landscape, and town planning, revealing how they “come together at the level of the street and make an impact on young Black lives” (p. 37).

White begins her study with an exploration of Newham and Forest Gate’s history, illustrating the critical relationship between Newham’s past and present. She explains how much of Black Britain reflects the country’s colonial endeavors abroad, drawing from the migration stories of both Caribbean and Black African migrants in Newham beginning in the 1950’s. This migration was followed up by encounters of structural racism and violence against these groups. Looking for jobs in manual labor at the end of the second world war, Black and minority migrants in Newham had unequal access to both employment and housing through restrictive work practices and long-term residency requirements by the Newham Council Housing policy (p. 13, 15). As a scholar grounded in mobilities research, I found the author’s ability to highlight the initial relationship between racial ideology and colonialism, movement (migration patterns), and structural racism a significant contribution.

In chapter two, White explores the onset and emergence of the neoliberal paradigm alongside the 2008 global economic crisis and its impact on Black lives. The neoliberal paradigm came about due to a number of economic crises in the 1970’s ushering in a neoliberalist era at the turn of the decade. With this new agenda came conservative values of “individualism” and competition alongside policies such as “the right to buy” legislation, favoring the wealthy. White then explains how, in addition to the cemented legacy of neoliberalism, the British government began a strict austerity policy cutting spending in vital public services. This, White argues, increased the inequality between the wealthy and the poor, where some ethnic minority communities were impacted, such as with the increase in youth unemployment rates (p. 28). Considering this, it would be interesting to examine the emergence of this paradigm and its evolutive policies impacting youth within other urban national settings across Europe.

The central argument of the book rests on the idea that Newham is a “place of contrasts and contradictions” prefaced at the end of Chapter 1 and examined further in chapters 3–5. In Chapters 3, 4, the author describes how Forest Gate can be broadly reduced to the narrative of “separate together”. The contrasting sub-local identities of grime and hip-hop and the WOW community (well-off workers) reveal a distinctly divided landscape at the hyper-local scale, contrary to the dominant narrative of the “urban village” pushed by the Newham council development strategy. White explains how the local council development plan for regeneration (“gentrification”; town planning) renders invisible the resistive strategies of musical expression produced by Afro- and Afro-Caribbean youth and the spaces that produce them via the sonic landscape (p. 55). I found this strikingly similar to the musical creatives produced in other global cities such as in the United States (New York, Los Angeles, Chicago) and in France (Paris, Marseille).

White concludes by discussing three ways in which violence – slow/fast, structural, or symbolic – manifests in the everyday lives of Black youth and minority communities through government policy. White effectively demonstrates here how “violence, [in its myriad forms (enforced anti-immigration policy, policing, strict monitoring/surveillance, and racial acts of terror)] occurs against a backdrop of five decades of a hostile environment that has erased and ignored the contribution that Black citizens have made” (p. 91). What stood out most to me in this chapter was White’s reference to “the plight of Black youth in the United Kingdom” (p. 86), particularly in its relation to other national contexts. Similar experiences concerning youth in the French setting with “racism in education” (p. 88), “issues of police brutality and high unemployment” (p. 93), and the “myth of equal opportunity” (p. 116) beckon key sites of comparison (see Piser, 2018).

While there is, at times, a lack of clear structure in the presentation of conceptual themes outlined in chapter 2, the research design undoubtedly succeeds in achieving the author’s stated goals. Through her analysis of the ways in which social forces and processes work in tandem impacting young black lives, White conclusively illustrates the underlying forces behind widening inequalities and poverty in urban settings specific to the global North. More broadly, her research reiterates how youth, and the urban poor, are at the forefront of understandings of local communities, the politics of belonging and citizenship, and geographies of inequality, revealing the paradoxical nature of the contemporary city. Therein, this book offers significant value for scholars and researchers in the fields of urban geography, sociology, planning, and public policy and notably intervenes in relation to other key urban ethnographic works such as “Streetwise” (Anderson, 1990), “In Place, Out of Place” (Cresswell, 1996), and “The Cosmopolitan Canopy” (Anderson, 2011).