We want to start these comments by extending deep thanks to our reviewers for their generous engagement and feedback, both in this review symposium and in the 2021 American Association of Geographers’ “Author Meets Critics” session that preceded it. That they carved out time to respond to our scholarship, even as the COVID-19 pandemic dominated and complicated so many aspects of life and work, means so much. We also thank Urban Geography for making this space for us, a year after the book’s release, to collectively think through the ways that A People’s Guide to the San Francisco Bay Area speaks to the field. In responding to our reviewers’ comments, this essay is focused around three central ideas. We consider the meaning of the public-facing structure of our book. We explore ways in which collaboration made the book, and, ideally, continues to shape the way that it lives out in the world. Finally, building from comments from our reviewers, we consider some possibilities for pedagogy that we see in the book’s structure and content.

First, we would like to engage with the question of how this book can be read, or used by different audiences. While it is designed, like all books in the People’s Guide series, to appropriate and subvert the format of a tourist guide book to a city, A People’s Guide to the San Francisco Bay Area makes a potentially frustrating guide book for anyone trying to plan a tourist weekend. Our book won't necessarily reveal the best spot for a selfie at an iconic vista or the hottest nightspots for consuming all the city has to offer. Instead, we highlight places like the South Bay’s Gold Street Bridge, a place in which historical significance may not be immediately obvious. For those that make the trip out there, we’ll walk you through some of the clues that mark this bridge as spanning a deep divide with buried histories: Alviso, a beautiful but disinvested place on one side of the bridge, looks across to the opulent futurism of Silicon Valley on the other. When we followed those clues, we found ourselves working through layers of local history, from the agricultural migrations that created worker settlements like Alviso, to the economic relationships that shape the Bay Area today. We hope readers will wander the place, with respect, and learn to read the signs of place and power. So, we bring you along with us, but we also ask readers to do some work.

In this way, the book is not offered as a definitive take on the region, and in fact we would argue that such a thing cannot exist. Instead, we view it as a guide towards a series of questions, an outlook, which may help reveal the signs of true placemaking, rather than the making of places for sale. Our book engages the Bay Area as a place in which to enact and live those questions. At face value, then, the book challenges mainstream tourist narratives of San Francisco, and it is our hope that the format – which we think of as scholarly work presented in the form of a guide – signals that it is meant for a wide set of publics. At the same time, we mean for the structure to engage a broader conversation on the practices of critical urban geography in the very places that it lives, out in the city itself. We see this as one of our core interventions within the field of geography: it may be that much of the work of understanding places needs to happen in those very places.

The collection of reviews here flatter our book’s engagement with urban geography via cultural landscape studies, place, and critiques of racial capitalism, and we appreciate how those connections are seen and made – in some cases beyond what we originally intended. We hope that we’ve done this in a way that enables readers who may not already be well-versed in scholarly theories and methods to see that they too are, or can be, producers of knowledge about urban geography through their own experience and critical observations.

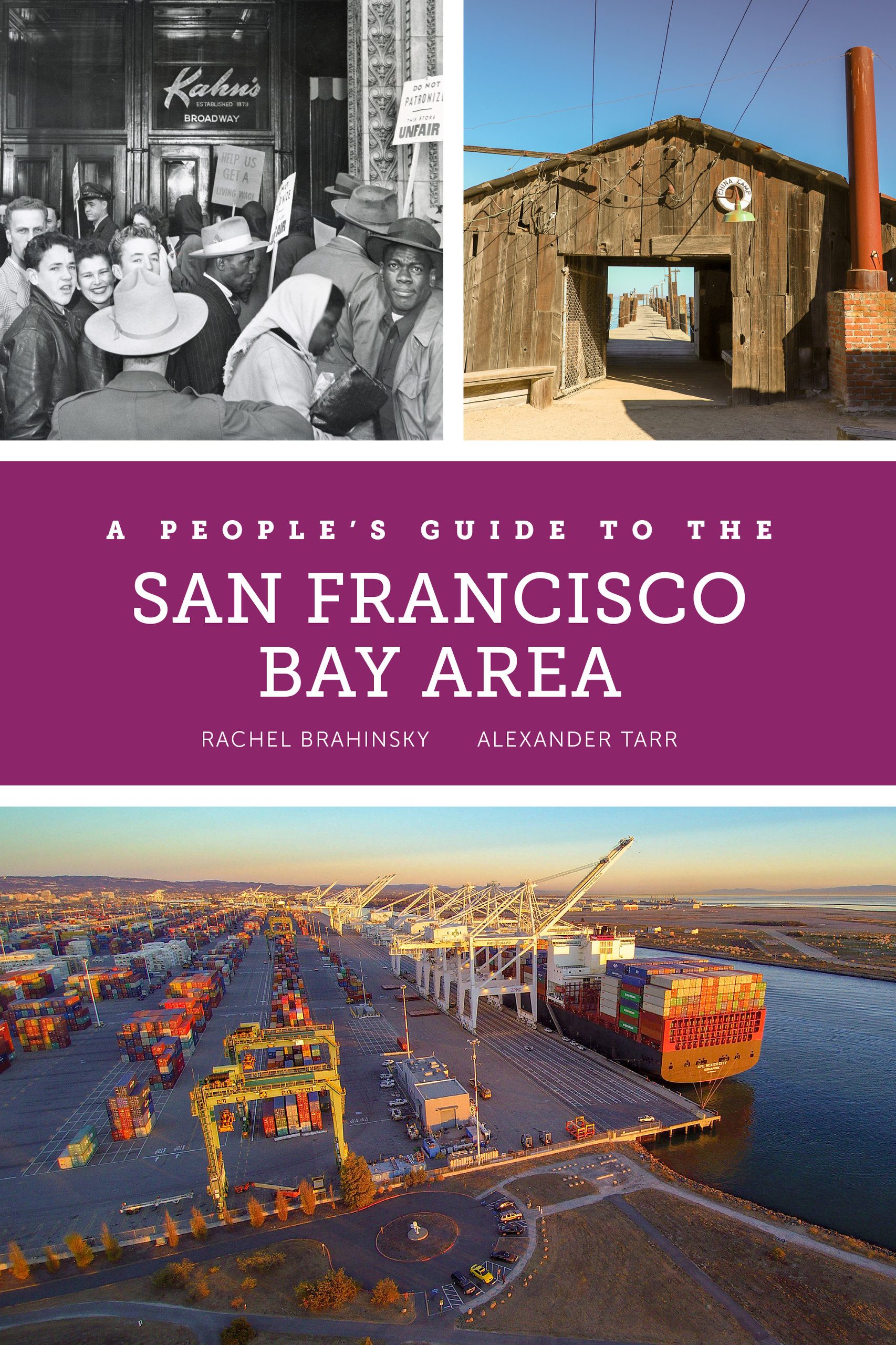

This connects to our second point about the different ways collaboration is woven through the work of this book, from its production all the way through (we hope) each time it’s picked up by a reader. While our reviewers note that we co-authored much of the book, we want to emphasize contributions from an incredible group of Bay Area scholars who offered their essays, photography, and research assistance–all of which we edited to give the book a cohesive voice. Those contributions, alongside Bruce Rinehart’s photographs and Alex Tarr’s maps, shaped our thinking about the enterprise of a “people’s geography” writ large. An important piece of this, for us, is the part we may never know in detail, which is what happens when readers take the text and use it out in the world. We focused on certain stories of each site, but we know that there are many more stories that matter about each place. We hope that people will be moved to document those stories, and that the broader work of learning with places and communities is boosted by our book.

Finally, we would like to highlight a point referenced in our reviews: the promise of our guide as a pedagogical tool. While we certainly hope the book is read and used by individuals, we want to highlight its potential use in collaborative learning environments, as an alternative textbook for the situated study of urban geographies. The introduction to the book lays out our approach to understanding an urban region via the relationships between sites, stories and forces that produce the cultural landscape. The book then provides dozens of examples of the kinds of knowledge those methods produce. In this sense, readers need not be students or residents of the Bay Area to find the book useful.

At the same time, the volume really is meant to provide a very different kind of survey of Bay Area geography than someone studying the region might usually encounter. In lieu of famous namesakes and important dates to be committed to memory, and eschewing abstract models applied to whole regions, we hope that the book invites students to grapple with the complexity of intersecting narratives that give the Bay Area an always dynamic sense of place. Meanwhile, as with any project, we are acutely aware of the book’s limits and what it is missing, in no small part due to the geographic and historic scope of the project. Still, beyond our own hopes and ambitions for A People’s Guide to the Bay Area, we are again grateful for the ways of reading and thinking with the book that the reviews included in this book review symposium make possible.

Rachel Brahinsky & Alexander Tarr Politics & Urban Studies, University of San Francisco Earth, Environment & Physics, Worcester State University